|

|

This article was published in

the American Bee Journal in August 2009.

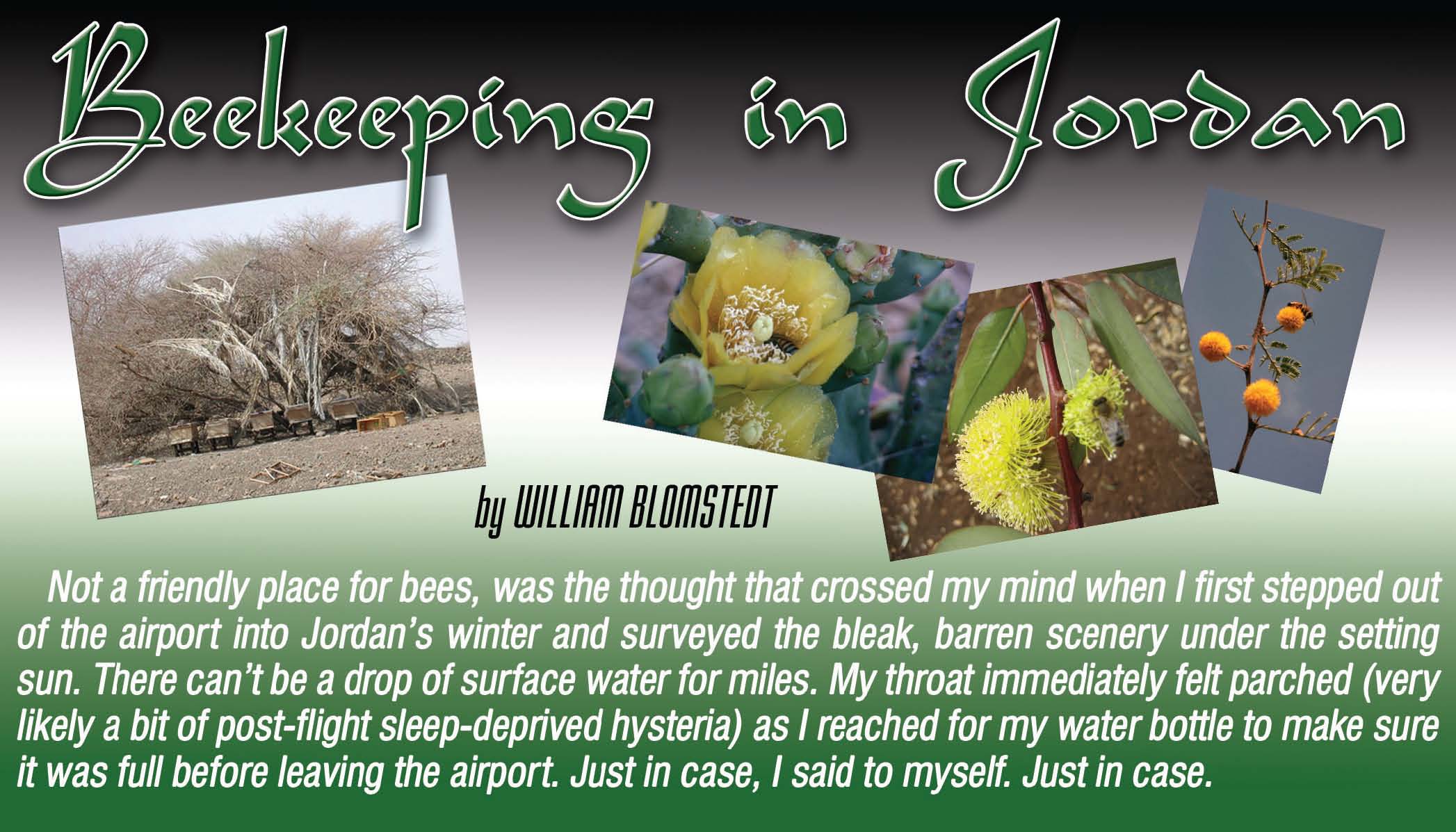

he landscape seemed hopeless and nude. The earth stood naked, and had no qualms about it. That moment in time leaned on me as my mind raced to catch up with the distance my body had traveled in the past 12 hours. The desert immediately put me, a water-loving forest-dweller, in a state of minor discomfort. This place was not going to welcome me with open arms, and if I suddenly were without today’s conveniences of water, food and shelter, I would be helpless as a drone in the late fall. The Bedouins, Jordan’s desert no-mads, would find my bones on their trek to the Dead Sea. he landscape seemed hopeless and nude. The earth stood naked, and had no qualms about it. That moment in time leaned on me as my mind raced to catch up with the distance my body had traveled in the past 12 hours. The desert immediately put me, a water-loving forest-dweller, in a state of minor discomfort. This place was not going to welcome me with open arms, and if I suddenly were without today’s conveniences of water, food and shelter, I would be helpless as a drone in the late fall. The Bedouins, Jordan’s desert no-mads, would find my bones on their trek to the Dead Sea.

Some days later, in a conversation with a few Jordanian students, I learned that each spring the rains come and the land is cov-ered by a green coat of life. “Everything turns very beautiful”, they assured me. But this Eden lasts only two weeks, and then the new growth is scorched by the relentless sun and the landscape returns to sand, rock and dust. Hmm. The color green was far beyond the conjuring of my culture-shocked imagi-nation. I settled onto a bus seat and let my mind drift over the reds and oranges on the way to the city of Amman. I spent the next few days visiting friends and walking the streets of the hilly capital city before heading south to seek some respite from the arid climate. Turns out I picked the wrong direction; it is possible to travel for hours on Jordan’s main automo-bile vein, the Desert Highway, and not see anything more than a lone tree or two in the small, sandblasted towns along the way. Then, as I reached the city of Aqaba, Jor-dan’s only seaport and beach destination on the Red Sea, a swift change took place. Hours of staring at the vast uninhabitable desert space was swiftly interrupted by the rush of humanity and artificially-watered life. Inside the city borders I saw public gar-dens and hotel grounds where flowers bloomed profusely and life flourished with the help of a network of irrigating systems. As I wandered around the public garden, it did not take long to spot what I was looking for - a small Apis hard at work. But, oh my! After spending weeks looking at Buckfasts and Italians in the apiary in Texas where I work, this specimen was not what I nor-mally associate with a honey bee. This little girl was . . . little, and brightly striped. She was hard at work and unconcerned with my presence, soon to buzz off to the next order of business. It was my first Apis florea, who, I found out later, is also a newcomer to Jor-dan. With my first bee sighted, I set off to find out more about these hard-working in-sects who put the honey in “The Land of Milk and Honey”. I went to visit Dr. Nizar Hadadd, the director of the Bee Research Unit, in the capital city Amman. After a twenty-minute cab ride from the city, I walked up the steps of the angular government office building. I wandered through white-walled corridors until I found bee propaganda decorating the walls, and poked my head into the nearest office. Dr. Hadadd, wearing a neatly-trimmed mus-tache and an argyle sweater, was discussing a thesis title with a female graduate student. He ushered me inside to a seat and contin-ued the conversation with the student, half the time speaking Arabic to her and then switching fluidly into English to ask about me and my stay. He burst forth with enough energy and enthusiasm to carry on both con-versations simultaneously and, when the student left, he focused all of his energy on me. Dr. Nizar’s ebullience expanded further as he revealed the multitude of projects and ideas he is working on in his quest for im-proving beekeeping, not only for Jordanians and Arabs, but for the international commu-nity as well.

Dr. Nizar Haddad in front of the National Center for Agricultural Research and Extension (NCARE)

Traditional beehives in Jordan

Jordan

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a small country nestled in a region of heavy conflict and contention. Its 55,900 square miles (making it about the size of Iowa) are set squarely at the crossroads of three con-tinents in the Cradle of Humanity. Imagine, those of you from Iowa, living every day with a prolonged war in Minnesota and rocket attacks on Kansas City. It is not a place for the faint of heart. In modern times the Kingdom has managed a steady peace with its neighbors, allowing it to earn its oft-toted moniker: Switzerland of the Middle East.

The Swiss comparison soon runs thin, however, as no snowy mountains are any-where to be seen (though I imagine Swiss yodelers and Muslim muezzins, the vocally-talented individuals who sing the haunting “call to prayer” five times a day, might get along well). Geographically, the Kingdom is divided into three natural regions running north to south: the Jordan Valley, the Upland area and the Badia Desert. For such a small area, these regions show a remarkable amount of biodiversity, supporting over 2,500 species of blooming plants. On the border of Israel is the Jordan Valley, which boasts a Mediterranean climate. Hot, rain-less summers and mild, moderately rainy winters combine with fertile alluvial soil to make it seem that anything can grow year round. The area between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea produces the majority of the Kingdom’s food and hosts the most

colonies of bees during the winter. The cen-tral natural region is mountainous and semi-arid. Most of the people of Jordan live here, in the cities of Amman and Irbid. Further west, the Badia Desert covers much of the country and is largely uninhabitable and barren.

Beekeeping

History

Beekeeping has been a farm enterprise in the Middle East since ancient times, thanks to the hardy nature of the native bee species

Apis mellifera syriaca. Excavated shards of pottery and carvings depict the rules of bee-keeping for the different civilizations that inhabited this area. In the town of Madaba, just east of the Dead Sea, I came upon the oldest known map of the Middle East, which is a tiled mosaic on the floor of a Christian church. In one corner, a Cupid is sticking his head into a skepshaped con-tainer with bees flying around, obviously angry at the intrusion. Traditional beekeeping used cylindrical tubes of fired clay or sun-dried mud and straw. As late as 1979 more then 80% of colonies in Jordan were still kept in traditional hives, but as the frame hive was introduced, the clumsy clay tubes fell by the wayside and a 2005 survey showed over 98% of bees are kept in Langstroth hives.

Current Status

In 2003 there were approximately 3,000 beekeepers in Jordan who kept 60,000 hives. Having learned this fact, my initial post-airport thought about this being a hostile landscape for bees was shattered: the

Chart 1 | Category | Number of Colonies | % | | Hobby Beekeeper | Fewer than 10 | 60 | | Part-time Beekeeper | 10-25 | 10 | | Full-time Beekeeper | 25-100 | 20 | | Professional Beekeeper | 1011000 | 9 | | Large-scale Professional Beekeeper with shop and employees | More than 1000 | 1 |

Ahmad Bataineh and Osama Migdadi in the Irbid Extension extracting room (r) The Irbid apiary behind bars

The Oriental wasp (Vespa orientalis) alive and a jar of collected dead. bees apparently survive as well as the humans do. Chart 1 shows the uneven distribution

in the types of beekeepers in Jordan. Sixty percent of

beekeepers are hobbyists who keep fewer than 10 colonies,

while large commercial beekeepers (over 1,000 colonies) are

scarce. The commercial farmers even practice some migratory beekeeping,

but the majority of beekeeping is still done by small

farmers in order to supplement their normal income. Honey From 1980 to 1998 honey production ranged from 50 and 200 tones per year. The two main honey-flows occur in the spring, one coming from the Jordan Valley citrus trees, and the other from the mountainous areas. The average domestic consumption reached 379

tones per year. The Kingdom imports about 282 tonnes a year, which means that domestic production meets only 20% of national consumption. But this statistic does not reveal the entire picture. According to Dr. Hadadd, Jordanians

prefer and value local honey as it is interwoven with spiritual and healing practices. In the Koran, Allah gave honey to the people for healing purposes. In the Bible, Solomon was a known honey fan and he recommended honey to his son. John the Baptist was eating Jordanian Honey in the Jordan Valley and, after the resurrection, Jesus ate honey and fish with his disciples. Honey becomes something more then a food; it is a mysterious and mystical sub-stance. Religion and history run deep in the Middle East, and religion is connected in some way to most everything in the area, even honey. The fall honey crop in Jordan comes mainly from the shrub Ziziphus spina-cristi, which became Christ’s thorny crown. I thought about that, for some reason, every time I ate a spoonful of Jordanian honey. Ziziphus spina-cristi. Often a family will have both local and foreign honey in the home. The local honey will be used for medicinal purposes: treating cuts, cough, allergies and improving energy. The imported honey will be used for daily consumption and as a sweetener. This preference is reflected in the price as well; imported honey reaches US$5 per kg, while the price of local honey is US$15-20 per kg. Honey Bees Apis mellifera syriaca is the indigenous honey bee throughout the eastern Mediter-ranean region: Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Syria and Lebanon. This bee is character-ized by a bright yellow color, small size, nervousness and is notorious for an aggres-sive defense. This aggression would make one think it might be preferable for commercial beekeepers to switch to less defensive strains such as Italian, Buckfast or Caucasian bees. In wet years, when water is abundant and the flowers are aplenty, bee-keepers with European bees congratulate themselves on their globalism. But when the water disappears and the flowers wilt, these same beekeepers lose the smiles and find themselves out of business. The European bees cannot survive such heat and so little water. Jordan is in the jaws of a near-decade long drought and is considered one of the four poorest water-resource countries. Good luck, Buckfasts. The syriaca is well-adapted to survive the extreme summer temperatures when there is a dearth of nectar. Unlike other non-native species of bees, syriaca is able to adjust its brood pattern to survive the extreme heat. The syriaca also shows more defensive behavior against the parasitic mite Varroa destructor and is better adapted to withstand attacks from the Oriental wasp (Vespa orientalis), both of which plague the European varieties. The wasp is a deadly enemy of the honey bee and a group of these giant wasps will ruthlessly destroy a Euro-pean hive. Syriaca have the remarkable ability

to smother an intruding wasp and kill it by elevating

the temperature to a fatal degree. Sadly, due to a half-century of foreign bee importation and interspecies breeding, pure syriaca bees are now difficult to find. Jordanian bees face the same diseases the rest of the world’s bees contend with: American and European foulbrood and Nosema, to name a few. The wax moth Galleria mellonella,Varroa destructor and the Vespa are concerns as well. The country has yet to see the Small African Hive beetle, though there are fears it may make its way to Jordan from Egyptian exports. Recently a new bee species, Apis florea, has come to town. Apis florea is a dwarf honey bee that is originally native in South-east Asia. Florea has been expanding its range steadily westward via natural and human transportation, but was unable to reach the Mediterranean region due to the desert barriers provided by Iran and Iraq. Because Aqaba and its sister Israeli city Eliat are major shipping ports, it is believed that florea was transported and introduced through the ports in recent years. Dr. Hadadd participated in the process of identifying florea in Jordan, but he is still unsure whether or not the small bee will be able to spread from Aqaba to other parts of the country.   Eucalyptus forest planted at Irbid extension Dr. Nizar and collegues looking at a syriaca hive in Irbid

Apis mellifera syriaca Bee Research Unit In 2002, the National Center for Agricultural Research and Extension (NCARE) of Jordan established the Bee Research Unit (BRU) in response to the increasing interest and demands of the beekeeping sector. With the main goals of (1) improving apiculture in Jordan, (2) conducting basic and applied research and (3) transferring new technologies

to local beekeepers, the BRU began with very limited, local

sources of funding. Dr. Nizar Haddad, the current director

of the BRU, began his work in 2002 and has developed the unit to international recognition. The BRU deals in both the scientific and social realms of beekeeping. In the scientific world, Dr. Nizar recently was awarded a Vita Research grant to study honey bee viruses. Haddad also received a new grant from the USAID to study the prevalence of Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus (IAPV) and other honey bee viruses in hives thought to have perished from the mysterious Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). Some scientific publications show that IAPV have a strong but possibly non-causal association with CCD, and Nizar’s upcoming research will hopefully shed more light on the situation. He has received grants and worked with USAID

on improving honey bee performance through pollen supplements and evaluating Jordan’s wild plants as a food source for honey bees. Nizar also continues to con-duct research on the syriaca. This sub-species of Apis mellifera has a very strong grooming behavior and a tendency to resist the varoa

mite and other honey bee diseases. Nizar started this work

in the year 2003 with the support of two German granting

organizations Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbait. Future research is planned to explore this concept. On the social side, much of the work of the BRU and Dr. Nizar is spreading the

knowledge, economic benefits and joy of beekeeping to as

many people as he can reach. In seven years, BRU has become

the reference for training of Iraqi, Yemeni, Palestinian and

Lebanese beekeepers, and is visited by beekeepers, extension

workers and researchers from the Arab world. Recently, the BRU conducted several clinics for Iraqi beekeepers, sponsored by organizations

such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Iraq Agricultural Extension Revitalization Project. These Iraqis come from their country to spend a week in Amman for lectures on basic beekeeping, honey bee diseases and queen rearing before traveling to an extension farm to spend two weeks of hands-on training. The BRU also hosts free beekeeper trainings for Jordanians. The classes are limited to 12-20 students and fill rapidly. The demand is greater than the BRU is able to fund. Though the country is largely arid, and much land is disappearing into urban sprawl, Dr. Nizar believes that the local flora can support more beehives. BRU is promoting beekeeping to smaller beekeepers as a means of generating income, especially for women. These hobbyists and part-time bee-keepers can sell their honey to neighbors or friends. To promote the hobbyists, the BRU provide free syriaca queens to Jordanians. The BRU hives in the extension apiaries hold some of the last pure strains of syriaca and they provide these free to Jordanians to try to increase local genetic resources and discourage importing queens. The demand for queens is greater than BRU is able to supply, and foreign bees are still imported. Dr. Nizar was the first Arab to receive an award from Apimondia. He won a Gold

medal in 2005 for the best instructional CD and two bronze

medals in 2007. Most recently he has translated Joe Beeman’s book Buzz about Bees

into Arabic, as well as compiled an English-Arabic

dictionary enabling bee knowledge to spread to the Arabic- speaking part of the world. In my time spent with him, Dr. Nizar repeatedly stressed how much he welcomed cooperation among students, beekeepers and scientists for study and research. Irbid In addition to the main offices of NCARE on the outskirts of Amman, there are seven extension apiaries located in different geo-graphical regions throughout the country for research and training. In this network, Dr Nizar, two research assistants, six technicians and five beekeepers are able to keep the organization running. One station I was able to visit was outside the northern city of Irbid, Jordan’s second largest city. Ahmad Bataineh and Osama Migdadi, two extension workers at the station, gave me a tour of the place, proudly showing the class-rooms, laboratory, extracting equipment and apiaries. The beehives were locked in an area enclosed by a metal fence, which gave them a “Do Not Touch” aura, making me curious about their famed defensive behavior. Ahmad dashed my hopes and advised that we not dig into the hives for fear of up-setting the bees on a cloudy winter day. I could still see a few syriaca flying around and working on the few blooming flowers in the area. A nearby grove of pistachio trees lay dormant and the olive trees had not yet sprung to life, but the pink almond flowers were the current Apis hot spot. The most interesting part of that visit was seeing the experimental forest planted by the extension. The BRU planted a number of different Eucalyptus spp., very hardy trees from the Australian outback that can survive in Jordan with very little water. NCARE has imported 15 species of Eucalyptus and this selection of trees flowers at different times of the year, allowing for bees to continue gathering nectar and pollen when there is no native honey flow. This forest is an essential stop for Jordanian bee-keeping classes; it encourages the beekeepers to plant these hardy species of trees on their property, thereby making the country more bee-friendly. NCARE is also experimenting with imported and local hybrid trees, as well as medicinal and ornamental plants. After the tour concluded we returned to offices and to drink tea and rest. The tea appeared

quickly and highly sweetened, as fit with the Jordan

tradition. It was not sweetened with honey though, but with a few heaping tablespoons of sugar per glass. One sip would make my heart start to race and my eyes bug out a little. I never found out why honey and tea were never mixed. Both Ahmed and Osama spoke excellent English and after a little more discussion about bees our conversation drifted until I found my-self, an hour later, discussing how T.S. Elliot had a major influence on modern day Arabic literature. I had never read The Wasteland, or knew anything about Arabic literature for

that matter, but it was comforting to communicate easily with these men. Many of the Jordanians I met knew bits of English; usually remnants of what they learned in school or picked up from movies. Every day I would have broken conversa-tions with people, as we tried to communicate using hand gestures and the 20 Arabic words I had picked up. Usually they would ask me what I did for a living. First I would say “beekeeper”, which would draw a puz-zled look; not a word in their vocabulary. I would then try to impersonate a bee, with body motions and even sound, often with comic and misunderstood results. Later on, I learned the Arabic word for honey (A’sal), but somehow I could never pronounce the word correctly. In front of the a is a myste-rious, throaty “H” sound, not available in my vocal palette. After saying “beekeeper” failed, I would say a’sal a few times only to get a confused look in return, especially as I choked, chortled and coughed. Finally I would give up and say “farmer” or we would just drift off into the barrier wall of silence in our communication gap. We would smile sheepishly at each other until I would say my favorite Arabic word, “mumkin” (which rhymes with pumpkin) meaning “maybe”. At this, people would usually smile and appreciate my effort to learn some of their language. We would shake hands and part, both happy that we had gained, at least, crumbs of friendship from someone vastly different. While I was in Jordan the war in Gaza smoldered and Barack Obama was sworn into office as the new president of the United States. The world seemed small as both events received intense coverage on every TV in every coffee shop and restau-rant I passed. The change in U.S. leadership was warmly received in Jordan, and the peo-ple I met seemed ready to give America an-other chance to build on a relationship that soured in recent times. Jordan, with its British influence and relative peace, has the potential to act as a bridge between the strained ties of the West and the Middle East. In their way, with translated texts and teaching, Nizar and the BRU are performing the same task in the beekeeping world by enabling communication between both sides and encouraging all forms of cooperation. In spite of their modest operation and lim-ited funding, they have been able to achieve some remarkable results in a land sur-rounded by conflict. Hopefully our world is willing to reach out and meet them halfway. Mumkin. William Blomstedt is a 2007 graduate of Dartmouth College. He is presently employed by B. Weaver Apiaries in Navasota, Texas, and traveled to Jordan and Egypt in January of 2009. Many thanks go to Dr. Nizar Haddad, Ahmad Bataineh and Osama Migdadi for their hospitality and for serving as a resource for this article.

Arabic beekeeping poster

|